Madihah Karim reflects on a recent visit to Baqa’a Refugee Camp in Amman, Jordan, which is home to over 130,000 Palestinian refugees and has evolved from a temporary shelter into a semi-permanent urban settlement.

She shares insights into how UNRWA’s education and health systems sustain daily life amid ongoing funding crises, highlighting the imminent challenges facing the future of Baqa’a and its residents.

A Town Within: Visiting Baqa’a Refugee Camp

The term ‘refugee camp’ can be thought of as inherently attached to the idea of temporality: an interim outcome of unexpected surges in civilian displacement and human insecurity during times of war. Baqa’a refugee camp has certainly been described as such, historically recorded as one of six ‘emergency’ camps set up in 1968 to accommodate refugees from across Palestine – forced to flee from the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza strip – during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War.

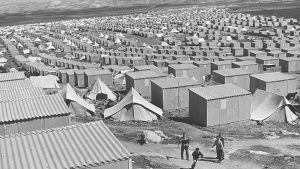

Today, the camp is akin to a small town or suburb, one absorbed by Amman’s urban spread, distinguished by the cramped buildings and narrow streets. Gone are the tents and temporary shacks that comprised the camp at its foundation (see picture).

Image: The 12-sqm prefabricated UNRWA shelter given to each refugee family across Palestine camps within a grided layout, Baqa’a camp, Jordan (Credit: Unrwa/Photo by G. Nehmeh, 1969)

While this gives a strong sense of long-term stability and integration, its infrastructure is still essential given the ongoing humanitarian crisis facing Palestinian refugees, almost six decades on from its conception.

With four colleagues from the PeaceRep programme, I was recently given the opportunity to visit Baqa’a. We were first welcomed at the head office by representatives from the Jordanian Department of Palestinian Affairs, who are responsible for the camp’s administration and security. This is no small task. As one of the largest Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, Baqa’a is home to over 131,630 registered refugees in an area of 1.4 square kilometres.

A map on one of the office walls indicated various districts and neighbourhoods within Baqa’a camp, named after Palestinian cities and towns such as Ramallah and Nablus. This cartographic representation reinforced the idea of Baqa’a no longer just being a site of humanitarian containment, but operating as a microcosm of Palestine, where national identity is continuously reimagined and reproduced across generations.

Following a brief introduction, our visit was conducted under the guidance of officials from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). As a service-oriented humanitarian institution, UNRWA occupies a unique and complex role in the Palestinian refugee experience, providing essential education, health care, and social services within the camps and across the broader Palestinian territories.

Beyond its operational mandate, the agency functions as a key intermediary between displaced communities and host governments, shaping both the material conditions of daily life and the broader politics of refuge and return. The result of UNRWA’s wide scale efforts is a paradoxical existence—what scholars have described as a condition ‘between exile and incomplete belonging’—where Baqa’a has evolved into a semi-permanent urban settlement while remaining discursively and administratively defined as temporary.

Schools and the Education System

For the first part of our visit, we were guided through one of the UNRWA-run schools in Baqa’a Camp. The building was modest but vibrant, its concrete walls softened by the energy of hundreds of children moving between lessons. The soundscape was instantly familiar — a mix of laughter, chatter, and the rhythmic call of teachers trying to restore order. Along the corridors, colourful display boards celebrated student work: hand-drawn maps of Palestine, embroidery-inspired patterns (tatreez), and collages of traditional dress and landmarks like the Dome of the Rock. Each classroom seemed to carry a small trace of home. The headteacher who welcomed us, along with the senior staff, were themselves Palestinian refugees, having experienced the same UNRWA primary schooling in this or other camps. The UNRWA official noted that less than 1% of the agency’s staff are international employees, highlighting the predominantly local composition of its workforce.

Baqa’a today hosts 16 UNRWA schools operating on a double-shift system to accommodate more than 14,000 students, from early primary through preparatory grades. Of UNRWA’s approximately 30,000 staff members, 18,000 are teachers. Despite there being 4,000 teachers in Jordan alone, resources are stretched as there is a high demand for education among Palestinian refugees in the camp.

The school was marking World Mental Health Day, signalling a significant shift from past stigmatization towards recognizing mental health as a critical public health issue. A dedicated section in the corridor aimed to educate children on the importance of mental well-being, offering practical strategies to manage stress and emotions. Among these, primary school students were guided in performing mirror affirmations. It was heartwarming to hear one of the teachers describe these affirmations as both relating to the value of life and capabilities as young, bright students.

This emphasis was particularly poignant given Israel’s ongoing military aggression in Gaza. Many students have family members who have been killed or injured, and the harsh realities of the situation are inescapable. Parents find it increasingly difficult to shield their children from the ongoing crisis. This current trauma resonates with the historical experiences of displacement during the 1967 escalation, perpetuating a cycle of psychological distress across generations.

In response to these challenges, the number of school counsellors has increased from one per 2,000 children to one per 1,200. UNRWA officials noted this was in part due to generous support from the Japanese government. As of March 2023, the Government of Japan contributed US$33.2 million to UNRWA, with US$5 million allocated specifically for Jordan to enhance human security for Palestine refugees. This funding supports critical services, including mental health initiatives in schools across the country. While this is a notable improvement, the ratio remains insufficient to meet the growing demand for mental health services.

Health Systems in Baqa’a

Image: PeaceRep at Baqa’a Camp Health Centre. (Credit: Madihah Karim).

For the second part of our visit, we walked through the town towards a health centre. The building was much more modern and well-maintained, equipped with basic medical furniture and equipment and the clinic itself was busy but well-organised. Here, the Director of the Hospital met with us and talked us through the provision of free, primary healthcare, maternal and child health services, and vaccinations for a population of over 80,000 refugees. He was particularly proud of the high-quality neonatal care, noting the only specialist care is in gynaecology. Mothers are supported with both pre- and post-partum checks. The health centres also integrate mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) into primary care, reflecting a growing recognition of the psychological impact of displacement, intergenerational trauma, and ongoing violence in Gaza and the West Bank. Children and adults alike can access counselling services.

It was enlightening to observe how the health system provides an administrative structure that extends across the camp. For instance, while vaccinations are not mandatory, their uptake is nearly universal because they are a prerequisite for accessing education services within the camp. This policy effectively integrates health and education services, ensuring that children receive necessary immunizations to attend school. The clinics also take a family-centred approach with entire families being invited for consultations, reducing the risk of individuals being overlooked in the system. This model also helps in maintaining accurate health records.

However, the limitations of health service provision cannot be understated. There are only two UNRWA operated health centres in the camp. Specialist services, including surgeries and advanced diagnostics, are not available within the camp’s health facilities. To address these needs, UNRWA collaborates with Jordanian health authorities and local hospitals. This partnership allows for referrals and treatment of complex cases that cannot be managed within the camp’s facilities. However, access to these services can be challenging for underprivileged refugee households due to high costs and logistical barriers.

UNRWA and the Future of Baqa’a

The term refugee camp seems inadequate in the context of Baqa’a. Schools, health centres, and mosques are woven into the urban fabric, giving the camp the infrastructure of a small town. Electricity poles, satellite dishes, and the hum of daily activity reinforce the sense of permanence. Walking through Baqa’a, one sees children in school uniforms, vendors calling out from corner shops, and families gathering in courtyards. There is a rhythm of life that reflects both resilience and community. And yet it is apparent: the camp remains framed by the surrounding desert, far removed from the bustling city of Amman. One third of people in the camp are living below the poverty line, restricted in their ability to work and build a sustainable life in Amman, with longing to return to their homeland underscoring the transience of life in Baqa’a.

From our visit, it was clear that access to education, healthcare, and basic services relies almost entirely on UNRWA and other humanitarian organizations. UNRWA’s mandate, renewed every three years by the UN General Assembly, is what allows Baqa’a Camp to continue functioning as more than just a collection of shelters. While the camp itself physically exists regardless of the mandate, it is this ongoing authorization that keeps schools running, health clinics staffed, and infrastructure maintained. In many ways, it is a lifeline that enables development within the camp.

This highlights the human implications of the crisis that UNRWA is facing today – by far the most significant in its history. The agency is facing a huge funding shortfall which presents an imminent threat to the camp. This ongoing volatility in financing highlights the structural vulnerability of refugee healthcare and education, making access to comprehensive services contingent not only on need but also on the availability of international support. The withdrawal of US funding across the humanitarian and development system accelerated the financial vulnerability of UNRWA, with current financial reports indicating they will only be able to maintain operations until the end of November, 2025.

It is hard to imagine the provision of essential services across the camp coming to a halt in the face of UNRWA’s financial deficit. The duality of the self-contained ‘camp’, a partially autonomous local unit while at the same time dependent on continuous foreign aid, gives Baqa’a its complex character: a community that has grown into a town while remaining in the shadow of exile.

Author: Madihah Karim is the Programme Manager at the LSE’s Conflict and Civicness Research Group. She holds an Masters in Theory and History of International Relations and works with various civil society networks on themes relating to Palestinian refugee rights.

Get the latest PeaceRep news, blogs and publications delivered directly to your inbox. Subscribe to receive PeaceRep’s monthly newsletter.